Using the MeerKAT radio telescope, a team of researchers from the University of the Western Cape, the University of Cape Town, Rhodes University, the South African Radio Astronomy Observatory and the South African Astronomical Observatory together with colleagues from twelve other countries have discovered a powerful megamaser – a radio-wavelength laser indicative of colliding galaxies. This is the most distant such megamaser found so far.

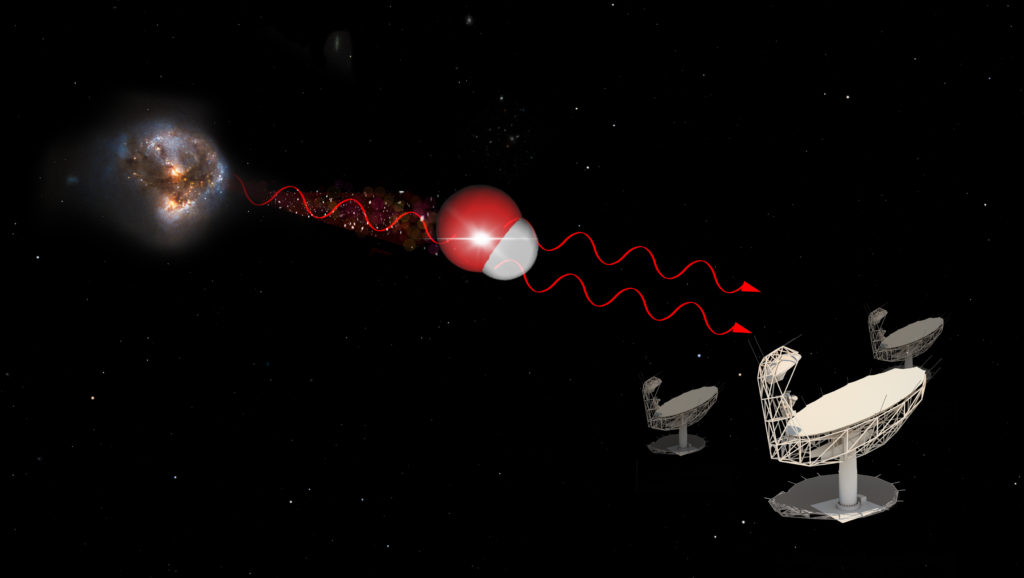

Galaxies are vast islands of matter in the universe. They are made of hundreds of billions of stars, gas and dark matter. When galaxies merge in collisions of cosmic proportions, the gas they contain becomes extremely dense. In particular, this can stimulate hydroxyl molecules, made of one atom of oxygen and one atom of hydrogen, to emit a specific radio signal called a maser (a maser is like a laser but emits radio waves instead of visible light). When that signal is exceedingly bright, it is called a megamaser. “When two galaxies like the Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy collide, beams of light shoot out from the collision and can be seen at cosmological distances. The OH megamasers act like bright lights that say: here is a collision of galaxies that is making new stars and feeding massive black holes,” explains Prof. Jeremy Darling from the University of Colorado in the United States, a megamaser expert and co-author of the study.

Hydroxyl megamasers emit light at a wavelength of 18 cm. This light belongs to the radio part of the electromagnetic spectrum, and it is the type of light that the MeerKAT radio telescope in the Karoo is designed to capture exceptionally well.

The LADUMA (Looking at the Distant Universe with the Meerkat Array) team leads one of the big MeerKAT science experiments, which is looking for neutral hydrogen gas in galaxies in one area of the sky, and looking for it very deeply – meaning very far from us, both in space and in time. By measuring the neutral hydrogen gas in galaxies from the distant past to now, LADUMA will contribute to our understanding of the evolution of the universe. This is no minor exercise, and so the research team comprises scientists from South Africa, Australia, Chile, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, South Korea, Spain, the UK, and the US. “LADUMA is probing hydrogen within a single ‘cosmic vuvuzela’ that extends to when the universe was only a third of its present age,” says Associate Professor Sarah Blyth from the University of Cape Town.

To look for hydrogen, the team looks for light with a wavelength of 21cm that has been stretched to longer wavelengths by the expansion of the universe. However, light from other atoms and molecules is also present, and in their very first observation with MeerKAT, the team detected bright emission from hydroxyl molecules that had been even more stretched from its original wavelength of 18cm.

Dr. Marcin Glowacki, previously a researcher at the Inter-University Institute for Data-Intensive Astronomy (IDIA) and University of the Western Cape, and now based at the Curtin University node of the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR), led the investigation. He explains, “It’s impressive that in a single night of observations with MeerKAT, we already found a redshift record-breaking megamaser. The full 3000+ hour LADUMA survey will be the most sensitive of its kind.” When they saw this signal in the data coming from the telescope, and confirmed that it was coming from hydroxyl, the team realised that they had a megamaser on their hands.

To make this discovery, the team had to run complex scientific algorithms on large amounts of data. This was made possible by the Inter-University Institute for Data Intensive Astronomy (IDIA) research cloud computing facility. This facility exists to help the South African research community do as much science as possible with the MeerKAT, and with the upcoming Square Kilometre Array in the future. Indeed, it is one thing to collect a lot of data, and another to work with it.

Facilities like IDIA’s are imperative if astronomers are to do as much science as possible with the MeerKAT, and with the Square Kilometre Array in the future.

Once the team knew it was a megamaser, they went on to look for its host galaxy. Where was the megamaser coming from? The patch of sky explored by the LADUMA team has been observed in X-rays, optical light and infra-red, so the team was able to easily identify the host galaxy. The team also knew that such a powerful, distant megamaser needed a good nickname, and invited members of the public to offer suggestions. The winning suggestion was “Nkalakatha,” an isiZulu word that means “big boss,” which was suggested by Zolile Tibane, a student from Johannesburg who is studying computer science at the University of the Western Cape.

The host galaxy of “Nkalakatha” is known to have a long tail on one side, visible in radio waves. It is about 58 thousand billion billion (58 followed by 21 zeros) kilometres away, and the megamaser light was emitted about 5 billion years ago when the universe was only about two thirds of its current age. “We have already planned follow-up observations of the megamaser, and as LADUMA progresses we will make many more discoveries,” notes Dr. Glowacki.

This is the first time a megamaser has been detected at that distance from its emission at 18cm wavelength. The authors of the study point out that it is not surprising that they found such a bright megamaser, given how powerful the MeerKAT is, but the telescope is very new, so this find hopefully is one of many more to come. “MeerKAT will probably double the known number of these rare phenomena. Galaxies were thought to merge more often in the past, and the newly discovered OH megamasers will allow us to test this hypothesis.“ comments Prof. Darling.

Radio astronomy is entering a truly exciting time with the upcoming Square Kilometre Array and its pathfinder telescopes, including MeerKAT. Unplanned discoveries are starting to emerge from the unprecedented amounts of data these instruments collect. And with MeerKAT and IDIA, South Africa is right at the cutting-edge of astronomy.

Notes to the Editors:

The scientific results of this study are published in:

LADUMA: Discovery of a luminous OH megamaser at z > 0.5

Marcin Glowacki, Jordan D. Collier, Amir Kazemi-Moridani, Bradley Frank, Hayley Roberts, Jeremy Darling, Hans-Rainer Klöckner, Nathan Adams, Andrew J. Baker, Matthew Bershady, Tariq Blecher, Sarah-Louise Blyth, Rebecca Bowler, Barbara Catinella, Laurent Chemin, Steven M. Crawford, Catherine Cress, Romeel Davé, Roger Deane, Erwin de Blok, Jacinta Delhaize, Kenneth Duncan, Ed Elson, Sean February, Eric Gawiser, Peter Hatfield, Julia Healy, Patricia Henning, Kelley M. Hess, Ian Heywood, Benne W. Holwerda, Munira Hoosain, John P. Hughes, Zackary L. Hutchens, Matt Jarvis, Sheila Kannappan, Neal Katz, Dušan Kereš, Marie Korsaga, Renée C. Kraan-Korteweg, Philip Lah, Michelle Lochner, Natasha Maddox, Sphesihle Makhathini, Gerhardt R. Meurer, Martin Meyer, Danail Obreschkow, Se-Heon Oh, Tom Oosterloo, Joshua Oppor, Hengxing Pan, D.J. Pisano, Nandrianina Randriamiarinarivo, Swara Ravindranath, Anja C. Schröder, Rosalind Skelton, Oleg Smirnov, Mathew Smith, Rachel S. Somerville, Raghunathan Srianand, Lister Staveley-Smith, Masayuki Tanaka, Mattia Vaccari, Wim van Driel, Marc Verheijen, Fabian Walter, John F. Wu, & Martin A. Zwaan

accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal Letters. Preprint: https://arxiv.org/abs/2204.02523

LADUMA

LADUMA stands for “Looking At the Distant Universe with the MeerKAT Array.” The LADUMA survey is one of the MeerKAT large survey projects. LADUMA aims to study galaxy evolution by detecting the neutral hydrogen gas in distant galaxies, going back over the last 9 billion years of cosmic time.

Inter-University Institute for Data Intensive Astronomy

The Inter-university Institute for Data Intensive Astronomy is a partnership of three South African universities, the Universities of Cape Town, of the Western Cape and of Pretoria as well as the South African Radio Astronomy Observatory. The overarching goal of IDIA is to build within the South African university research community the capacity and expertise in data intensive research to enable global leadership on MeerKAT large survey projects and large projects on other SKA pathfinder telescopes.

MeerKAT

The South African MeerKAT radio telescope, situated 90 km outside the small Northern Cape town of Carnarvon, is a precursor to the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) telescope and will be integrated into the mid-frequency component of SKA Phase 1. The MeerKAT telescope is an array of 64 interlinked receptors (a receptor is the complete antenna structure, with the main reflector, sub-reflector and all receivers, digitisers and other electronics installed). The MeerKAT is built and operated by the South African Radio Astronomy Observatory.

https://www.sarao.ac.za/science/meerkat/

ilifu

Ilifu is a regional node, known as a Tier II node, in a national infrastructure, and partly funded by the Department of Science and Technology (DST) through their Data-Intensive Research Initiative of South Africa (DIRISA). It is a partnership between the University of Cape Town, the University of the Western Cape, Sol Plaatje University, the University of Stellenbosch, the Cape Peninsula University of Technology and the South African Radio Astronomy Observatory. Ilifu is built and operated by IDIA.

The Square Kilometre Array

The Square Kilometre Array (SKA) project is an international effort to build the world’s largest radio telescope, with eventually over a square kilometre (one million square metres) of collecting area.

Media Enquiries:

Dr. Carolina Odman

carolina@idia.ac.za

+27 (0)823028167

Dr. Marcin Glowacki

marcin.glowacki@curtin.edu.au

+61 423 486 919